Introduction to Graph Theory in the Context of Dual Polytopes

I just finished a presentation on graph theory for the math club I’m a part of, and I’ve wanted to write a post about it, but I’ve never actually put forth the effort to write it. Well, since I gave a presentation on it, and I made some sick slides, I thought I would write up a quick post.

First things first, I should narrow down my purpose. I would like to define graph theory for those not familiar with it, then I would like to move on to hitting some terms that come up in the general study of graph theory before moving on to a short discussion on what in the hell dual polytopes are. At the end, what I hope to have achieved is that you (the reader, if you actually exist) gain a better understanding of graph theory, not as an applied subject, but as a pure math topic studied just for fun.

What is graph theory? Well, in a word it’s the study of graphs.

Just not graphs of functions…

So sadly there’s a bit more to it than that. For the applied mathematician, graph theory graphs are a method of modeling some system that is composed of interconnected components.

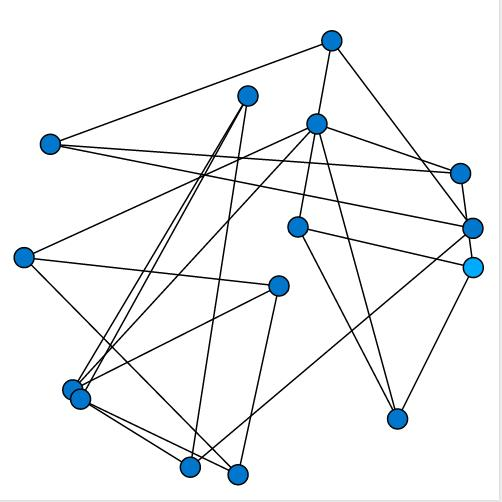

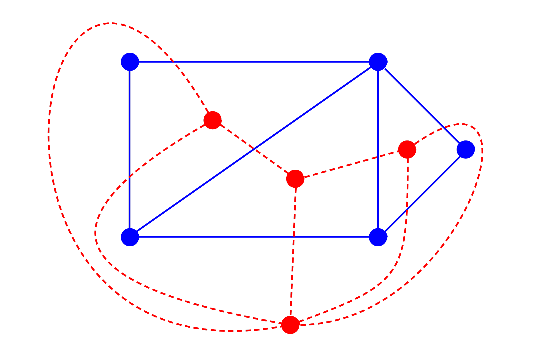

In this image, the blue dots (nodes, or vertices) represent some component of a system, while the lines between them (edges) represent the common relationships between the components.

However, I would like to examine graph theory from a more pure math perspective. The pure math view of graphs is not as a model at all. For pure mathematicians, a graph is composed of two pieces, a set of vertices, and a set of edges. The edge set contains two element subsets of the node set to represent an edge between two nodes.

In more formal words, A graph is an object made of two sets called its vertex set and its edge set. The vertex set is finite and nonempty. The edge set may be empty, but otherwise its elements are two-element subsets of the vertex set.

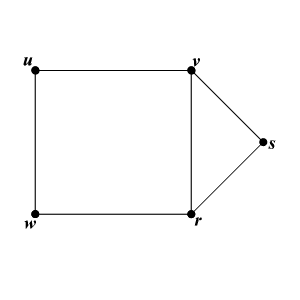

For example, the following graph has the vertex set and the edge set

I’ve chosen to draw the graph in 2 dimensions, with nice straight lines. However, does the above definition of a graph contain any information whatsoever about the shape of a graph? This is the distinction between a graph diagram and an actual graph.

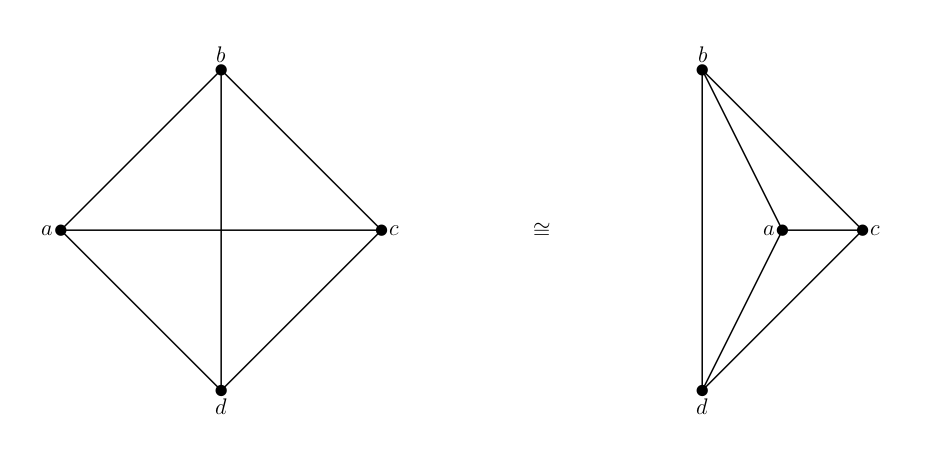

Let’s move on to some terms graph theorists throw around. One of the fundamental ideas in graph theory is the idea of isomorphic graphs. We say two graphs are isomorphic if there exists a one-to-one correspondence between their vertex sets such that whenever two vertices are adjacent in one graph, the corresponding vertices are adjacent in the other. isomorphism is denoted .

Isomorphism is a concept similar to graph equality, but has a subtle difference. We say two graphs ate equal if they have the same edge and vertex sets. This means that two equal graphs are in actuality two representations of the same graph. If two graphs are isomorphic, they are two separate graphs that have the same underlying structure.

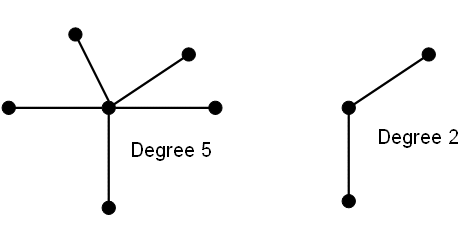

The degree of a node is the number of edges incident to it. Interesting story. Looking at the degree of nodes is actually how Euler solved the Seven Bridges of Konigsberg problem in 1736.

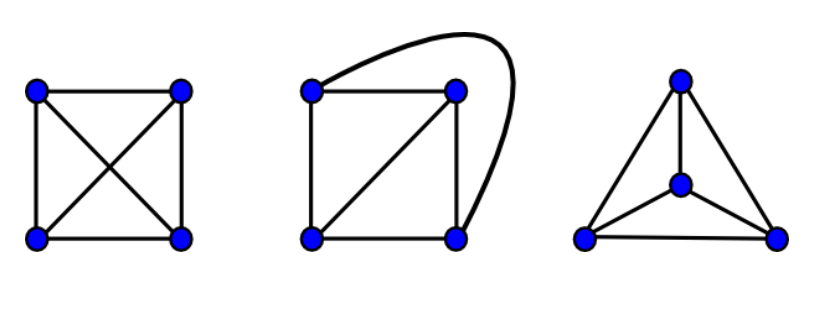

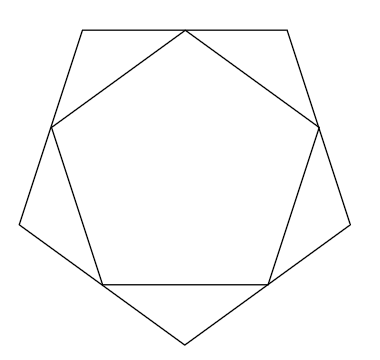

Now let’s get into some ideas that will help set the stage for understanding what in the hell dual polytopes are. We say a graph is planar if it is isomorphic to a graph that has been drawn in a plane (2D) without edge-crossings. Otherwise a graph is nonplanar. For example, these three graphs are all isomorphic to each other, and show that the graph they represent is planar.

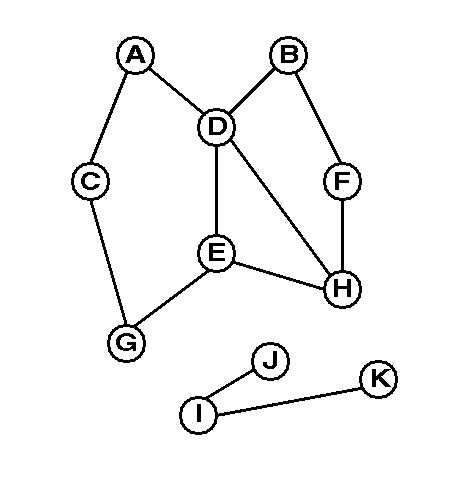

A graph is said to be conected if every pair of vertices can be joined by a walk. Otherwise it is said to be disconnected. A walk is a sequence of adjacent vertices. For example, in the following (disconnected) graph, is a walk.

When a graph is drawn on a plane without edge crossings, it cuts the plane into regions called faces of the graph. Note that the number of faces is independent of a particular drawing of a graph.

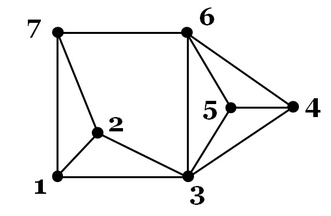

In this graph, there are seven faces, not six. Based on the above definition, the region surrounding the graph is also a face, even though it extends infinitely in every direction.

The above graph is also polygonal. We say a graph is polygonal if it is planar, connected, and has the property that every edge borders two faces. This means you can never have a polygonal graph with a node of degree one, as that would just stick out and not divide the plane into any faces.

Dual graphs are what we’re going to spend the rest of the post talking about. The best way to explain a dual graph is with a picture I think. In the following image, the red graph is a dual of the blue graph. Note that I said “a” dual, not “the” dual. It turns out that duals are not unique.

We can also see from this picture that the dual of the red graph is the blue graph (this is why duals are called dual)!

In more formal language, a dual graph of a planar graph is formed by taking a crossing-free plane drawing of the planar graph, placing a dot inside each face, and joining two dots whenever the borders of the corresponding faces have one or more edges in common.

Essentially, we’re replacing faces with nodes, and the borders between them with edges.

Now I guess we’re ready to start talking about polytopes. A polytope is a geometric object with flat sides in -dimensions. Polygons and polyhedra are examples of polytopes. Essentially, it’s an -dimensional version of a polygon.

Now an interesting question would be to ask if we can make graphs out of -dimensional objects. If you think about the set-based definition of a graph that I gave, it told us nothing about where the vertices in the vertex set are located. They could be on the Cartesian plane (), in normal 3 dimensional space (), or in ) in general. It is easier to think about graphs in 2 or 3 dimensions though, so that’s where we’ll start.

The simplest type of polytope is a polygon. Well, actually maybe a single point in is a polytope, but I’m not sure about that so we’ll just ignore that…

Polygons are planar right? We can draw them on a plane without edge-crossings. Regular polygons are what’s called self-dual. If we draw the dual of a regular polygon, we get a smaller version of that polygon back.

Now I’m kind of fudging a bit. When I talked about the dual of a graph above, that was all about the faces of graphs, but here, we’re replacing edges with vertices, and vertices with edges. This is actually the line graph of a polygon, but people smarter than me call polygons self-dual, so I will too. At this point, we’re thinking less about graph theory, and more about abstract multi-dimensional geometry.

So polyhedra are 3D, right? Can we redraw them on a plane so that there are no edge crossings? For simple polyhedra, called the five Platonic solids, we can, as you can see below.

As a thought experiment, to verify that 3D solids can, in fact be planar, let’s think about a simple shape, like a cube. We’re holding a cube in our hands, and it’s like a molecular model you might see in a chemistry lab. We’re holding it against our chest by the two outermost vertical edges. Now these are graphs we’re talking about, right? We can stretch them, and move them around as we please, so what we’re going to do is pull the cube against our chest until the cube is completely flat. Ultimately, it will end up looking something like the middle graph in the image above.

But wait, cubes have six faces, and I only see five in the image above. Well, kind of… remember I said graph theorists consider the region outside a graph to be a plane? That’s the sixth plane of our cube.

So this means that a cube is planar, what about the rest of the regular polyhedra? Well, in the style of a true mathematician, I’m going to assert that they are, but leave the “trivially obvious” proof to the reader.

What about -dimensional polytopes though? That’s a bit trickier, so I think I’ll be avoiding a discussion about that here.

So if 2D polytopes (polygons) are self-dual, are 3D polytopes (polyhedra) self-dual? Well, regular polygons have vertices and edges, so if we replace every edge with a node and every node with an edge, we end up with exactly the same graph!

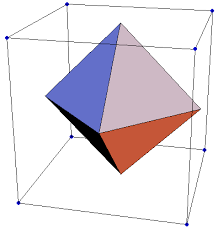

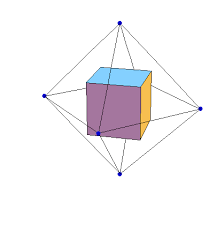

Let’s think about a simple 3D shape first, like a cube. But cubes have six faces, and eight vertices. So cubes cannot be self-dual. But we can still draw a cube and figure out what it’s dual is. This is easier to see in 3 dimensions than with a planar drawing, so that’s what the following image shows.

The dual of a cube is an octahedron, and as the following image shows, the dual of an octahedron is a cube.

If we wanted, we could draw both the cube and the octahedron as a 2D graph on a plane (they’re both Platonic solids), but it’s easier to see the intuition behind all of this if we draw it in 3D like you see above.

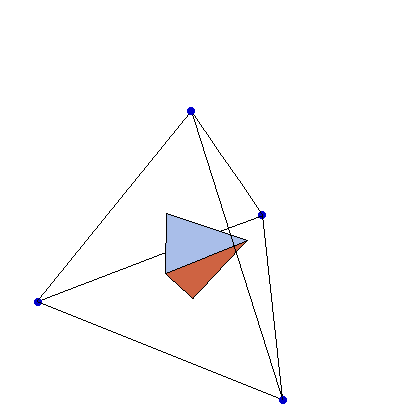

So the cube isn’t self-dual, but what about other Platonic solids? Let’s take the very simplest of them, the tetrahedron. If we draw the tetrahedron’s dual in 3D, it’s easy to see that it’s a tetrahedron.

Note that tetrahedra have four faces, and four vertices.

There are a number of other self-dual polytopes.

- Regular polygons

- Regular tetrahedra

- -simplexes (-dimensional triangel/tetraheda/pyramid thingys)

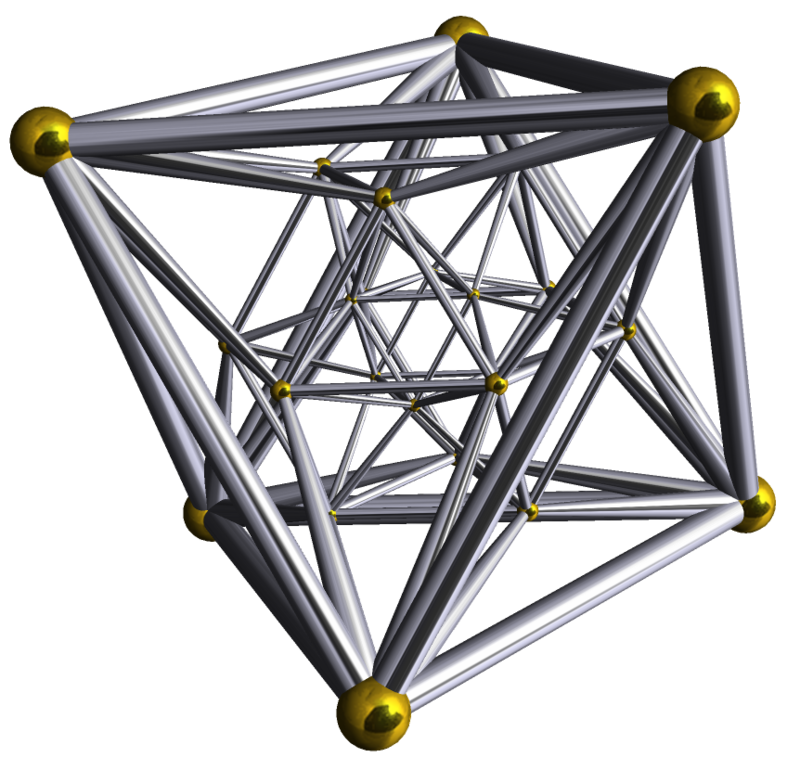

- regular 24-cell

- great 120-cell

For your viewing pleasure, here’s a picture of a regular 24-cell.

What about other polyhedra that I haven’t mentioned so far?

The last two Platonic solids, the icosahedron, and the dodecahedron, are duals of each other.

I said that all regular polyhedra are planar right? That means that we can find a dual for every regular polyhedron, whether it’s a Platonic solid or not.

What about in -dimensions though? Can we find duals for more complicated shapes? That’s really where I want to leave it, with that unanswered question, which will hopefully keep you up at night with it’s complexity.

If you found this interesting, you might want to Google a handful of these terms:

- Topology, surface families, the genus of a graph We said that planar graphs are graphs that can be redrawn on a 2D plane without edge-crossings, right? What if we were to redraw a graph on a 3D surface, like a cube, or a sphere, or a donut? Well, it turns out, if a graph is planar on a 2D plane, it’s also planar on a sphere, and vise versa. If a graph is planar on a sphere, it’s also planar on a donut (torus), but not vise versa. This is how we can relate topology with graph theory, and that’s an interesting topic in itself.

- Polyhedral combinatorics, discrete geometry, multi-dimensional geometry As a mathematical discipline, much of what we’ve looked at is less graph theory, and more geometry, so if you found this interesting, consider reading up on some of these.

- The differences between a graph’s dual, line, and face graphs. I mentioned I was fudging a bit when I said regular polygons are self-dual. If that interested you, check these out.

Surprisingly enough, the Wikipedia articles on these topics are a fantastic resource, and they’re hyperlinked together, so you can spend hours and hours procrastinating on that exam tomorrow morning that you haven’t studied for.